What I learned at Lunch about the Love of Jesus Christ

I attended the Catechetical Conference 2011 for the Archdiocese of Galveston-Houston this past Friday and it was pretty interesting. It is a conference that brings in speakers from all over the US to speak on a whole variety of topics that clergy and laity will find of interest in their apostolate of catechesis and formation.

I think the most interesting speaker was, far and away, Dr. Scott Alexander, the Associate Professor of Islam at Catholic Theological Union in Chicago, and is also the Director of the school’s Catholic-Muslim Studies Program. He gave the keynote address Friday morning on Islamic-Catholic relations, which he entitled, Confrontation and Dialogue.

He was a great presenter with never a dull moment and his scope of historical, cultural, religious and linguistic knowledge was incredible. He gave us a bird's eye view of world history and the good-and-bad relationship between Catholics and Muslims down through the centuries. For instance, one pope, St. Gregory VII, called the Muslims "our brethren" in religion. And then you have St. Bernard of Clairvaux who, in preaching another crusade, said that killing the Muslim "was not homicide, but malicide." Confrontation and dialogue, indeed!

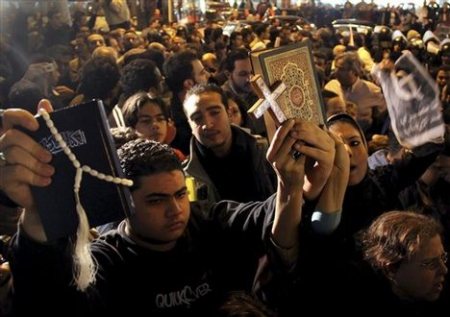

The protestors were united against a brutal regime, and they achieved solidarity in and through their faith, not in spite of it. Learn that lesson! (photo from WorldNews - http://wn.com/Egypt_Christian_Protest)He even got to speak on contemporary issues, especially what's going on in Egypt right now. He showed us a picture of an Egyptian Coptic Orthodox man holding up a cross next to a Muslim holding up the Koran, and how they are holding each other's hands. It was a gesture of solidarity.

The protestors were united against a brutal regime, and they achieved solidarity in and through their faith, not in spite of it. Learn that lesson! (photo from WorldNews - http://wn.com/Egypt_Christian_Protest)He even got to speak on contemporary issues, especially what's going on in Egypt right now. He showed us a picture of an Egyptian Coptic Orthodox man holding up a cross next to a Muslim holding up the Koran, and how they are holding each other's hands. It was a gesture of solidarity.

Something fascinating and under-reported: in the midst of the protest, the Muslims cleared a path for the Christians to gather and to celebrate Mass and the Christians made room so that the Muslims could pray.

At lunch my friend Brian Kelsch and I were able to sit down with the speaker and he let me pepper him with questions (he assured me he wasn't annoyed. He told us that he was actually delighted that he wasn't being called a heretic, traitor, terrorist-sympathizer, and/or unpatriotic).

After a while of asking really specific questions about Twelver Shiite Islam, sects in Pakistan, US foreign aid to Egypt, Jordan, Indonesia, Saudi Arabia and all those other dictators held in power with our tax dollars, he stopped us and said, "You know a lot about this stuff. That isn't normal. How do you know so much?"

Feeling pretty good about myself at that compliment, I said, "I was pretty pro-war until recently. I was and still am on the Right-wing of American politics and still claim the 'conservative' mantle from time-to-time. But I heard a liberal, anti-war activist say on a podcast that I listen to, that 'America is the only country on earth whose people have no idea who they are bombing.' I knew that described me. I knew nothing of Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Somali, or Pakistan, so I resolved to change that. Thus, Wikipedia."

Without missing a beat Dr. Alexander just looked at me and said, "You know, theologically speaking, we never know the people we are bombing. If we really knew them, we wouldn't be bombing them."

Without missing a beat Dr. Alexander just looked at me and said, "You know, theologically speaking, we never know the people we are bombing. If we really knew them, we wouldn't be bombing them."

The weightiness of that statement took a while to penetrate my rather thick skull.

A few minutes later Kelsch and I were talking about the lunchroom conversation we just had and he remarked how once we see someone else's dignity and know them as friends, it would be impossible to make war on them.

And that is, I believe, the heart of what the radical love of Jesus Christ is offering this tattered world: a love that not only knows no boundaries, but even pursues our enemies, going right to the center of that hostility and embraces our enemy as another self.

Chesterton once quipped (as he is one to do): "The gospel tells us to love our neighbor and to love our enemy. Probably because they are the same person."

I think Dr. Scott Alexander showed me something new in the Gospel at that lunchroom table. In those two little sentences he went beyond Chesterton and made me realize something I think I always knew, but refused my assent: The radical love of Jesus Christ bids us to love our enemies so much that we transform them (or really ourselves) into neighbors.

That is the love of our precious martyrs who, dying for the Gospel, loved and forgave those who were in the process of actually killing them. That is the love of a Son who begs, who cries out from the darkness of the Cross, "Father forgive them, for they know not what they do."

Am I ready for that kind of love?